Plumtree School - Old Prunitians

Plumtree School - Old Prunitians

Plumtree School - Old Prunitians

Plumtree School - Old Prunitians

Information kindly supplied by Jill Baker, grand-daughter of Bob Hammond. Details excerpted from her book Beloved African the memoirs of her father, John Hammond.

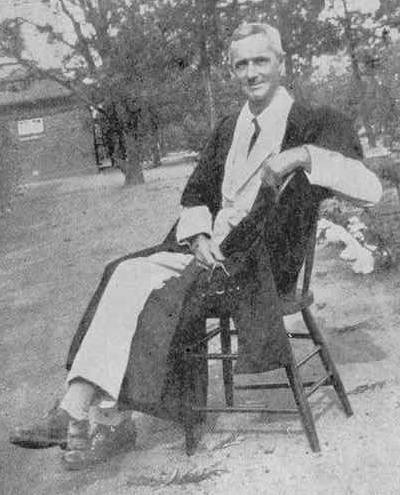

Robert (Bob) W.

HAMMOND, HEADMASTER 1906-1936

Bob Hammond, or "Tambo" as he was affectionately

known, went on to become a legend in Rhodesia instilling the best

of British education and moral rectitude into his pupils in this

far flung and remote corner of Empire.

Bob was born in Liverpool in 1876 and brought up in

Toxteth at the time his father was working with the ragged

schools. He was educated at Liverpool College and then went up to

Peterhouse at Cambridge to take his degree in ethics and

philosophy.

After that, he spent some time tutoring the son of the renowned

artist, Val Prinsep, in Pevensey at the same time as his best

friend Keigwin was tutoring Osbert Sitwell. Anthony Prinsep

subsequently became John’s godfather, giving him a beautiful

silver rose bowl at his christening. Prinsep was well off and

well known and owned a couple of West End theatres. John met him

only once when he was asked along to a "very posh"

restaurant. He didn’t remember much about the meal or the

man – except that he tipped the waiter enough to feed the

then undergraduate, John, for at least a week… but

didn’t give his godson a penny.

However, they did discuss Bob of course, and Prinsep said he

clearly remembered, as a very young boy, seeing him with two

others, having just been recruited into the Imperial Yeomanry,

preparing to go out to the Boer War. The family never heard much

about his war, but at one stage Bob was taken prisoner. As the

Boers could not feed them all, 800 of them were released with a

few bags of boermeal and told that if they were seen in the next

24 hours they would be shot.

Bob managed to meet up with English troops despite a fairly

severe wound to the right arm and hand. The rest of his life was

spent coping with indigestion as a result of the undiluted

boermeal and doing most things left-handed.

After the war, Bob returned to England, taught at schools in

Eastbourne and Hull and while in lodgings in London, met a

determined wee Scots lass, not quite five foot tall, Harriet

MacEacharn. From his academic and rather serious perspective, he

quickly fell in love with an absolutely irrepressible sense of

humour, a bright and lively mind and a very considerable musical

ability.

Harriet MacEacharn had led a very genteel life – with the

exception of the last few years. Her father was part of a large

Scottish family, which hailed from the isle of Islay. The family

boasted a direct line back to Flora McDonald, the lass who helped

Bonnie Prince Charlie escape by rowing him across a loch. The

"dark" side of the family history was the infamous and

rascally Black Baron of Kilravock.

Bob Hammond became one of Harrie’s boarders at the time he

was tutoring the Prinsep boys. He was seven years her junior and

it was an immediate attraction of opposites. The tall, gentle,

aesthetic and academic young Englishman and the irrepressible,

artistic and tiny wee Scot. Their courtship continued for a

couple of years, during which Bob went off to the Boer War. She

wrote at the end of 1900:

My own precious darling boy, I was so glad to have a

long letter from you last week and the photo, which is simply

splendid. Of course it is a wee bit dark but you do look nice. I

haven’t seen anyone half so nice since you went away. I am

so thankful to know that you are safe where you are tho’ I

cant help being just a wee bit anxious…

Then just before Christmas of the same year, she

wrote:

It is hateful to think of Xmas being

so near and that I shall have to spend it without you. I wonder

why there was no letter from you last week. I wish I could keep

from feeling anxious and miserable when I don’t hear from

you as I know it isn’t always possible for you to write

– indeed it is quite wonderful how you have managed to do

so… (Bother! Here’s that Frenchman coming upstairs to

give Madeline a lesson and her ladyship has forgotten all about

him and gone out to dinner).

Harrie’s strength and character is clearly reflected

even in these short sentences and Bob was blissfully devoted to

her from the time they met. When at one stage, he plucked up the

courage to send Harrie a cable saying he had received a job offer

in South America. Her rapid reply read: "Choose South

America or me!"

When the next offer came to live in Africa – and as

Harrie had always nurtured a vision of herself careering wild and

free on horseback over the plains of Africa – she accepted

gracefully.

Bob’s father married them in St. Swithin’s Church,

South Hampstead in 1902 and Bob left for Africa six weeks later.

Their marriage and partnership became one of the foundation

stones of European education in the new country of Rhodesia.

A new life in Africa

Harrie joined Bob in South Africa in 1903. He had a job as

a schoolmaster and was the local magistrate in Amsterdam in the

Eastern Transvaal. Two years later, his friend from university

days, H. S. Keigwin, recommended him for the headmastership of

Plumtree at 300 pounds a year, plus board and lodging. It was 100

pounds a year less than he had received at Amsterdam – but

it held such a huge challenge ! As such, it was irresistible.

In 1904, Harrie at the age of 38 had given birth to their first

child, Ian, always known as Skinny, followed by young Bob two

years later… precisely six weeks before they left for the

long trip up to Plumtree. It was a brave move for a woman who had

not been in the country long, who was now over 40 and who had two

very small children.

They were at least able by that stage, to travel by train rather

than the more usual and much slower ox wagon. But even this was

an exhausting, dusty trip. The line had not yet been metalled, so

the engine would stir up a cloud of dust, which would envelop the

rest of the train as it went round corners. Even with

temperatures well into the 100s windows and doors had to be

closed to contain at least some of the dust.

History does not recall what her reaction was to seeing Plumtree

in 1906 – but she must have been horrified. Whatever she

felt at first, she set about her first priority, which was simply

carving the family a comfortable and livable home in the original

old thatched pole and dagga huts. She then went on to

become the heart of the school’s music, theatre and

hospitality.

Once Harrie arrived, the village had not only a pianist but also,

its first piano. She had brought over a little Collard and

Collard from England and every time the family went to the farm,

the first thing that was loaded onto the ox wagon, was the piano.

She played by ear and she played all the time. She only had to

listen to something once and she could sit down and play it and

transpose it up or down at sight, as required.

Bright, rotund and no nonsense, Harrie, was the perfect foil to

Bob – she was the yeast to the dough, the sparkle in the

wine. She knew just how to pop in the apt and realistic remark

that would make Bob’s dreams achievable. They were closely

integrated with the school so that home and school became

completely intertwined.

She remained loyally Scottish to the end. John recalled with

great love: ‘She was a remarkable woman… widely read

– musically very well educated – with a great sense of

humour and an abundance of love and affection.’

She was the ideal mother for a family of five – or, as was

more usual, 50. The huts simply expanded to meet whatever was

asked of them, whenever Harrie was around. From this outpost of

empire, she was the one who negotiated the rights to perform an

annual Gilbert and Sullivan production using the boys and staff

of the school and also produced and accompanied the first

production in 1912 of The Mikado.

Plumtree’s Gilbert and Sullivan productions were at that

time amongst very few amateur productions in the world permitted

to be performed outside London. The tradition continues today.

When he started at Plumtree, Bob Hammond had a very difficult job

and recent archives endorse just how hard it was –

especially for someone with the ideals he held for the young of

the new country. He was a highly self-disciplined man; self

controlled, passionately fond of the school and devoted to his

family. He was also supremely idealistic, a great thinker and

hard taskmaster. Reveille was blown at 5.30 a.m. each morning

with inspection and duties starting straight away. Bob was

determined to produce well-rounded boys of character, high moral

fibre and resourcefulness.

He was a great believer in his boys finding out about Native

customs and cultures, the bush, farming and nature study at first

hand. He also believed all boys should do manual work and they

soon built the school’s first playing and rugger fields in

this way. He insisted that every one had to find their own

strength, whether it was taking part in sport, in the highest

academic practices, cadets, learning bridge and chess, debating

and drama societies, the annual Gilbert and Sullivans or other

theatrical productions.

Within his first 18 months, Bob Hammond formed a Cadet Corps,

laid the sports fields, inaugurated the first school sports,

speech and prize giving days, started up debating and literary

societies and had many new buildings either planned or in the

process of being built.

Bob was also prepared, in the interests of the boys’

development, to take the risk of allowing them a tremendous

amount of freedom to go out into the bush – it was never

abused in the 30 years he was at Plumtree. They were encouraged

to go out and fend for themselves at weekends

– entirely reliant on their own initiative and resources.

They had to let the school know where they were going and there

were heavy penalties if that was not adhered to. The only other

stipulation was that younger boys had to go with older boys who

were responsible for their welfare and there were some protocols

about when they were considered able to "head up" a

group.

Before these bush trips, the schoolboys would do extra work in

the garden or on the new playing fields in order to earn salt.

The Natives didn’t like or trust money at that stage…

but salt would buy the boys almost anything they needed from the

Natives.

Plumtree boys grew up speaking the language like the natives

– they learned to track animals and they understood the

traditions and respects expected of them when they entered the

villages. The Natives were quite interested in this school

business but it made no sense to them at that stage when young

boys were of far greater value being trained as hunters and

herdsmen of their cattle.

From the early Hammond days, Plumtree produced by far the

greatest number of Europeans in the country, who later went on to

work directly with the Natives, in education or as Native and

District commissioners.

In the first and second decades of the century, provisioning a

growing school so far away from a centre of civilisation was

extremely difficult. Masters and boys had, not only to grow all

their own foodstuffs, but in the early years to kill for meat for

the pot, as rinderpest was prevalent and cattle still died. To

provide the food for the school, as numbers grew, so far from

anywhere, the headmaster also had to become a farmer.

Bob bought a farm, Bush Hill, which was half a day’s ox

wagon ride away, as a means of growing crops and, once the threat

of rinderpest had passed, of raising cattle. But it also became a

great holiday home and every school holiday was spent down at the

farm – saving the family the cost of going off on holidays

elsewhere.

In later years, Bob developed this further and bought in cattle

and pigs, fattened them and slaughtered them for the school. In

order to do so, he had to raise a personal mortgage on an extra

piece of land. This became a great and troublesome financial

burden to him for the rest of his life as a result of which he

had enormous difficulties educating all his children beyond

Plumtree and keeping up with the payments. Fortunately, most won

useful bursaries or he would not have been able to educate them

as he would have liked.

In his attempts to mould his charges to men of leadership,

unafraid to face a challenge, Bob tried at one time, to change

the school clocks to "Plumtree Time" – an hour

ahead of others in order to make the most of the daylight hours.

After a few months of complete confusion, he acknowledged defeat

turned back the clocks and changed the hours of operation

instead.

In 1912, the school acquired a carbide lighting system to give

"real" lights to the chapel and schoolrooms while

candles and paraffin lamps were still used in the dormitories.

This new machine had to be pumped up at certain intervals and

boys were designated to take responsibility for this vital role.

The lights would grow dimmer – the hope and delighted

anticipation of the children being that they would be plunged

into darkness – before the boy on duty started pumping.

During Evensong one Sunday, the lights dimmed alarmingly and Bob,

in the full flow of his sermon, said very firmly in the

middle of an important theological statement, and without

interrupting the continuity in the slightest… ‘Pump,

boy, pump!’

In 1913, it was decided to close down the girls department of the

school with the few girls going to a school in Marula, a village

nearby. Plumtree began to establish a specific identity as a

school that trained and equipped male leaders of the future.

By 1915, the school’s reputation was such that it was

growing at a great pace with children coming from all over

Rhodesia and surrounding countries. As it grew, the problems

caused simply by its isolation, grew in direct proportion.

Water had always been a problem, with tank deliveries awaited

anxiously, baths were allowed to be only 1.5 inches deep with

bath water used in turn for garden and fruit tree watering. The

wells and tanks were under pressure and constantly running out of

water. After desperate pleas to the education department, with no

results or acknowledgment, a water tank once had to be hijacked

from a passing train to keep the school going.

A desperate shortage of money was an ongoing concern – and

with it the ability to attract good teachers to a perceived

"uncivilised" part of the world, "with no

guarantees of any continuous employment, no possibility of a

pension and small opportunities of promotion"!

Things became particularly hard during the 1914-18 war as all

his male staff joined up and it became very difficult to find

suitable teachers. He had, to a large extent, to employ older

retired men or women teachers who were not always the best at

controlling wild young teenagers.

The famous benefactor, Alfred Beit died soon after Bob took over

as headmaster. He had left 200,000 pounds in his will, for

"educational, public and other charitable purposes".

There was a scramble from assorted power brokers – all with

different ideas as to how this was to be administered. Bob played

a pivotal role in persuading the Trustees to assign a fund to be

put aside purely for the development of badly needed school

buildings and infrastructure throughout the country. This was

later on to be useful for Plumtree itself, as the present

buildings could not possibly cope with the anticipated increase

in pupils.

One of the first pupils at Plumtree in the days when it took both

boys and girls, Muriel Baraf (then Furse) told, in her book Recollections

of Plumtree School, of her return to the school in 1934, to

take over as Matron of Lloyd House, after a gap of 17 years.

She relates some wonderful anecdotes about the Hammonds and about

the school itself. She writes :

My arrival in Plumtree as matron of Lloyd House… filled

me with astonishment. When I last saw it, Plumtree was a dry,

arid spot with a motley collection of buildings. Now, there were

three houses for the boys, a dining hall with convenient catering

department, a properly equipped hospital, bright airy classrooms,

an administrative block, a fine Beit Hall with a stage and

gallery, pleasant houses for the staff and studies for the boys;

science and woodwork rooms, a well fitted-up laundry; three

playing fields, several tennis courts, a squash court and a

swimming pool, gardens, trees and lawns. These were the visible

signs of an exceptional school, pioneered by a genius for making

something out of nothing.

There was no water shortage now. Herbert Brooke, with a team of

African workers was building the dam, which was named after him.

The Hammonds now had a suitable Headmaster’s house.

As an adult I came to know the Hammonds very well and felt part

of the family. Things, which are now considered by many people as

of prime importance, such as fashionable clothes and expensive,

shiny cars, meant nothing at all to the Hammonds. They owned an

ancient, derelict Ford and I think that every time I went with

them in it something strange happened !

Mr. Hammond would always enjoy a joke against himself. One

Sunday, during the evening service while he was giving his

sermon, a "Christmas beetle" in a certain boy’s

pocket started singing. Mr. Hammond stopped and said, ‘Will

the boy who has a Christmas beetle kindly go out !’

Whereupon the whole school stood up and trooped out of Chapel !

Mrs. Hammond was entirely without pretence; and position and

worldly possessions meant little to her. ‘Och! What does it

matter!’ she would say. As she grew older, she was given to

little catnaps towards the end of the day. Bishop Paget had come

to Plumtree and after dinner Mr. Hammond had work to do in his

office and so left his wife to entertain the Bishop. As it was a

hot evening, they took their chairs outside. When Mr. Hammond

arrived an hour or so later, they were both fast asleep ! The

Bishop said afterwards that it was one of the most pleasant

evenings he had ever spent.

Mrs. Hammond never worried about her appearance and I doubt if

she ever troubled to look in a mirror. For a special occasion,

she was once known to put on her dress inside out. When someone

drew her attention to the fact, she replied, ‘Och, never

mind. The next time I’ll wear it the right way out and

people will think it’s a new frock!’

Very few people in Rhodesia were well off at the beginning of

the 20th century and a country schoolmaster was poorly

paid. Harrie had to use all her canny Scottish ways and

upbringing to make the budget stretch sufficiently to feed the

family.

John remembers his daily diet consisting in the main of mealie

meal (ground corn – staple diet of the Africans) and maas

(sour milk not unlike yoghurt), with chickens, game and the

luxury of milk and cream when they went away for weekends and

holidays on the farm. Harrie of course provided a daily ration of

oatcakes and scones, steamed syrup puddings and pies – all

good sound Scottish fare… in the heart of Africa. They

didn’t eat much in the way of fruit and vegetables –

because there was insufficient water to grow them in Plumtree and

they were so remote, that fresh produce went off before it even

reached Plumtree. Oranges and naartjies (mandarins) were grown

locally – but then people didn’t seem to have fruit and

vegetables as part of their diet to nearly the extent as they do

now.

The boys all wore khaki shorts, shirts, pith helmets and no shoes

– in fact John did not wear shoes as a regular thing until

he was 13 or 14. It suited the practicality of life at Plumtree.

Shoes were hard to get and they wore out too quickly in those

harsh conditions. It was a lot healthier to go barefoot in that

hot dry climate.

The boys at the school were always being encouraged to use their

initiative and to be prepared to step in at the last moment, or

follow up on ideas they had. John had just been made a prefect,

when he approached his father once to ask whether they could have

a common room.

‘Yes. Good idea – what are you going to do about

it?’

So John and his fellow prefects designed the common room, made

the bricks, and built themselves a common room, parts of which

still stand today following a succession of fires, usually

started as a result of the licence granted to senior boys, to

smoke.

In 1936, Bob and Harrie decided, following many agonising

discussions, to leave Plumtree after 30 years at the helm. They

knew it was time to move on, but they were both institutions of

the school by now and it was a tremendous upheaval for them as

well as for the people they would be leaving. Everyone tried to

persuade them to stay "just a little longer…"

John went down to the annual sports day, held over Easter in

1936. For Bob and Harrie, it was to be the last of these

memorable events and it became a formal valete to them both.

Three hundred people attended from all over the country and in

the time-honoured tradition, all the schoolboys gave up their

beds and camped out in the grounds, while parents and VIPs slept

in the dormitories. John wrote :

The weekend in many ways was rather trying, being the last

Sports at which Dad and Mums will be there as the Head. There was

much speechifying and several presentations from parents, old

boys, school, staff, village and others. I shall send you a copy

of the paper, which might prove of some interest to you.

The journey down on Thursday night was far from pleasant. The

train was packed and we had five in our compartment giving us

hardly any room to move. We got down about 11 o’clock, swam,

played squash rackets and caught up with long lost friends.

On Saturday we had the first day of the sports in the afternoon

and dinner in the Hall that evening, at which numerous and

lengthy speeches were made preceding "The Gondoliers"

put on by the school. It was well done, though the lengthy

speeches had left the wee brats dressed up on their war paint for

such a long time that they were dead tired when the show started.

On Sunday there were the normal Chapel services for Easter Sunday

followed by a presentation by the Old Boys to Dad and Mums. They

gave them a lovely suite of office furniture which, as the family

have very little in that line of their own, will come in very

useful. We followed this by a beer fight at which great

quantities were swallowed and which put most of us into a state

unfit for anything but sleep! In the evening, Dad gave an address

to the school and spoke better than I have ever heard him (see

Appendix 1). How they have managed to stop themselves breaking

down is more than I can say as they are both feeling this

departure very much. The Governor came down as a special effort

as it was Dad’s last… in the evening H.E. gave out

prizes amid more speeches… all very moving.

One of the country’s poets, George Miller wrote a poem

entitled "After 30 years… RWH":

and so the last hymn fades, and in the quiet he turns and

moves away; there’s an end.

so is the last word written when the book is done, so the last

rivet driven and made fast;

so, when the agony of hand and spirit’s over, is the last

stroke made and the wet brush laid by

and while each maker knows the sober joy that bathes the spirit

when the task is ended

in such simplicity, his heirs unborn enter their heritage. So man

grows rich.

I began to understand what made my John when I read some of

the eulogies written by old boys and politicians, judges and

priests. One of his staff, Arthur Cowling, wrote :

Hammond’s main guiding principle was a belief in freedom

for his boys in both thought and action; and he was always

prepared to defend this principle, which was consistently

pursued.

Boys were encouraged to take a close interest in and to discuss

fully all current affairs, not excluding political elections and

any other local controversial issues. He believed in taking a

"Newspaper" period with every form in the school for

such discussions, which constituted a valuable training in

citizenship. And he fostered self-government and personal

responsibility in every branch of school activity.

He delighted in argument and had the faculty of not allowing the

strongest official disagreement with a master to affect personal

relationship.

We might feel at times that discipline was too slack; particular

instances would lead to an exchange of strong views, addressed

officially; the correspondence would end with a note: Dear

……… come and talk this over on Sunday afternoon.

The talk might go on from early afternoon till late evening,

covering a walk of miles and one came away feeling that even if

all one’s arguments had not been adequately countered, one

was assisting a sincere and lovable man in an interesting

experiment, in which his view might after all be the right one.